What does Edmund Husserl have to do with the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience? Quite a lot, actually.

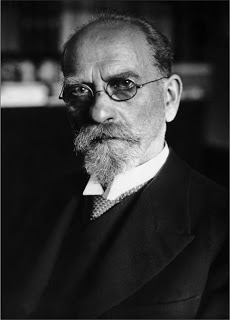

In the late 19th century Edmund Husserl was developing a way of doing philosophy that would get us “back to the things themselves!” Previous to him European philosophy had become either idealist/relativistic (in its Hegelian and romantic versions) or empiricist/reductionistic (in its British scientific and skeptical versions). Husserl wanted to reclaim “the things themselves,” to allow philosophy again to deal with reality, not just our projections (idealism) or our sense data (empiricism). To do this he founded (although not without help from his mentor, Franz Brentano) the way of phenomenology. If phenomenology can be expressed in two words they would be:

intentionality and

givenness.

Intentionality is the most well known part of phenomenology — it is the fact that “consciousness is always consciousness of something.”

“If we imagine a consciousness prior to all experience, it may very well have the same sensations as we have. But it will intuit [think] no things, and no events pertaining to things, it will perceive no trees and no houses, no flight of birds nor any barking of dogs (Logical Investigations I, section 23).”

Husserl argues that there is no plain old consciousness, there is no “blank slate” as it were of the mind, but that we are always conscious of things, conscious of something as something. All our thoughts have intentional content — these lights as a stop signal; those sounds as a fire alarm; that person as my wife. Things are not perceived neutrally but as things, and what these things are perceived as depends on my experience, background, traditions, etc. All thoughts are intentional — they are thoughts of something as something.

The second watchword for Husserl is givenness. Against the subjectivist notion of philosophy that says we project or create the meaning of the world, that we produce reality from our minds, Husserl maintains that it is the world that gives itself in intuition (thought as experienced). This notion of givenness is most famously put forth in Husserl’s “principle of principles:”

“Enough now of absurd theories. No conceivable theory can make us err with respect to the principle of all principles: that ever originally preventive intuition is a legitimizing source of cognition, that everything originally offered to us in ‘intuition’ is to be accepted simply as what it is presented as being, but also only within the limits in which it is presented there (Ideas I, section 24).”

What Husserl maintains here is that “the things themselves” are what dictate their terms to us; we do not impose meaning on the world but receive the terms of meaning from the things as they are given to us. We have different modes of knowledge and experience not because of our own subjective temperaments but because different things give themselves in different ways. A cube of salt gives itself to me differently than a advancing lion. In phenomenology I must pay attention to how something gives itself to me to find out what the thing is.

Okay, what does this have to do with religious vows? I think all three vows (poverty, chastity, and obedience) can be helpfully understood in terms of these two Husserlian notions: intentionality and givenness. For each vow this means paying attention to what the vow is referring to: just as thoughts are always thoughts of something, so too vows are not just vows but vows for something. And just as the things of the world are given to us in intuition, so too each of the vows gives to us something, presents something as given and only as given in a mode appropriate to the vow itself. Of course the ultimate given of each vow is Jesus Christ, and each vow allows Jesus to give himself to us in a particular way, as the poor Christ, the chaste Christ, the obedient Christ. We will in turn look at the phenomenology of each vow and the presentation of Christ in them.

But why is this important? Why is this not just another exercise in ivory tower academics? I think Husserl is helpful because when people ask me about the vows they almost always conceive of them as (1) an act of giving something up; and (2) an act that I choose to do. While it is good (or bad!) for my ego to have people lauding me for my “discipline,” “commitment,” and “sacrifice;” and while these aspects of the vows are true, I don’t think they are the primary reason for taking (or living) the vows. The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, bears witness to the true reason for the vows:

“The Church continually keeps before it the warning of the Apostle which moved the faithful to charity, exhorting them to experience personally what Christ Jesus had known within Himself. This was the same Christ Jesus, who “emptied Himself, taking the nature of a slave . . . becoming obedient to death”, and because of us “being rich, he became poor”. Because the disciples must always offer an imitation of and a testimony to the charity and humility of Christ, Mother Church rejoices at finding within her bosom men and women who very closely follow their Saviour who debased Himself to our comprehension. There are some who, in their freedom as sons of God, renounce their own wills and take upon themselves the state of poverty. Still further, some become subject of their own accord to another man, in the matter of perfection for love of God. This is beyond the measure of the commandments, but is done in order to become more fully like the obedient Christ (LG 42).”

The vows are not so much about giving up something as about opening up our lives to the reception of a gift given to us: Jesus Christ. The vows are not a negative act but the positive act of conforming ourselves more and more to Christ who has offered himself for us and seeks to abide in us more perfectly. In order to better understand how the vows conform us to Jesus Christ, I think Edmund Husserl and his thought can be a valuable companion, just as he was a valuable teacher to both St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) and Professor Dietrich von Hildebrand, and a major philosophical influence on Blessed John Paul II. So, let us get “back to the vows themselves!” Or perhaps better, to the One we know and love in them.

*see also:Phenomenology of the Vows: PovertyPhenomenology of the Vows: ChastityPhenomenology of the Vows: Obedience